The First ever Brooch

Discover the fascinating history of the brooch, from its humble beginnings as a Bronze Age clothing fastener to its transformation into a masterpiece of jewelry design across ancient civilizations and into the modern era.

The History of the Brooch

The First Brooch and the Evolution of Adornment

Brooches are often thought of as beautiful ornaments, but their story begins not with luxury, but with function. Long before gemstones and goldsmiths entered the picture, the very first brooches were simple pins designed to hold garments together. As human societies advanced, this modest invention evolved into an expressive art form, reflecting culture, identity, and status. Let’s trace the journey of the brooch from its earliest origins to its rise as a symbol of adornment.

The Humble Beginnings: Bronze Age Fasteners

The very first brooches emerged during the Bronze Age, around 2000–1200 BCE. These early designs were made from bone, wood, or bronze, and served a purely utilitarian purpose: securing cloaks, tunics, or other draped garments. Without buttons or zippers, these simple fasteners were essential for daily wear, particularly in colder climates where layered clothing was common.

One of the earliest surviving examples is a gold spiral brooch, dating from around 1600–1200 BCE, discovered in the Danube region. While this piece is more decorative than purely functional, it represents the transition from necessity to artistry. Even at this early stage, humans demonstrated a desire to combine usefulness with beauty.

The Rise of the Fibula: Ancient Innovation

By the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, brooches evolved into more sophisticated forms, most notably the fibula. Much like a modern safety pin, the fibula featured a spring, pin, and catch, providing both security and reusability. This innovation spread across Europe and the Mediterranean, becoming one of the most common accessories of the ancient world.

Fibulae were not just practical; they also reflected cultural identity. Greek and Etruscan fibulae took on distinctive shapes, such as the “spectacle” design with dual spirals, while Roman versions were mass-produced and decorated with geometric patterns. Their widespread use made them a canvas for artisans, who began experimenting with form and decoration.

From Function to Fashion: Symbolism in the Roman World

During the Roman Empire, brooches transcended their utilitarian roots to become symbols of status, style, and individuality. Crafted from bronze, silver, and gold, Roman fibulae were often inlaid with enamel, glass, or gemstones. The wealthier the wearer, the more ornate their brooch, making these accessories both practical tools and social signifiers.

The Roman “crossbow fibula,” for instance, became a staple of military dress, while disk-shaped brooches adorned with enamel were popular among civilians. These pieces not only held garments together but also communicated power, profession, and regional identity. Brooches had become wearable statements, carrying meanings beyond their mechanical function.

The Etruscan and Greek Flourish

The Etruscans and Greeks elevated brooch-making into a true art form. Between the 9th and 6th centuries BCE, their fibulae often featured intricate wirework, animal motifs, and elaborate shapes that blended beauty with symbolism. These cultures valued the brooch as both adornment and amulet, often imbuing designs with protective or spiritual meaning.

A striking example is the Etruscan fibula in the form of a horse with a monkey rider, dating from the Orientalizing period (720–580 BCE). Such pieces illustrate how brooches became more than clothing fasteners; they were miniature sculptures that reflected cultural mythology and craftsmanship. The brooch, by this point, had firmly stepped into the realm of wearable art.

Masterpieces of the Hellenistic Era

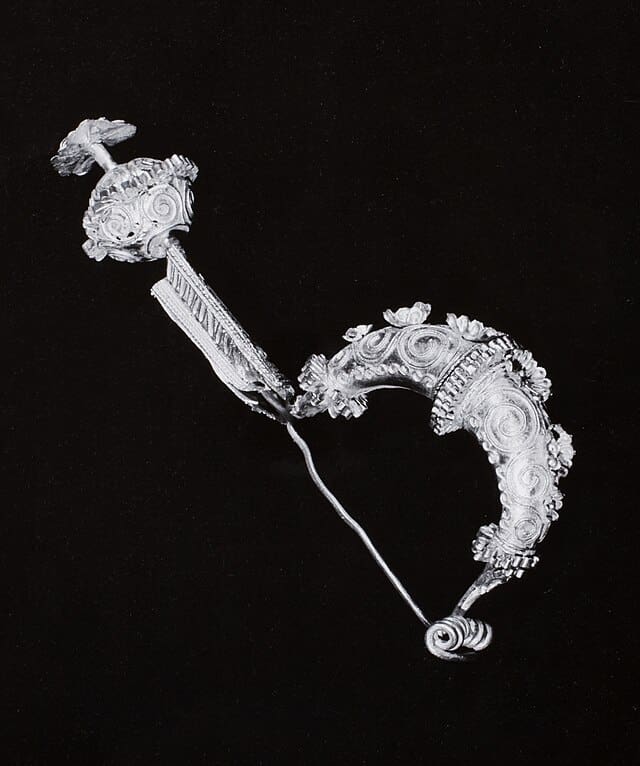

By the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE), brooches reached new levels of complexity and luxury. The famous Braganza Brooch, for example, crafted in the 3rd century BCE, depicts a warrior defending himself against a hunting dog, its terminals shaped like stylized canine heads. This extraordinary gold fibula, likely made by a Greek artisan in Iberia, reflects both technical mastery and narrative storytelling.

Hellenistic brooches were not only jewelry but also reflections of power and sophistication. Worn by elites, they blended mythological themes, naturalistic imagery, and fine craftsmanship. In these pieces, the brooch had transformed into a vehicle for artistic expression, standing alongside sculpture, coinage, and pottery as a testament to human creativity.

The Victorian Sentiment

Fast forward to the Victorian era, where brooches often carried deep personal meaning. Locket-style brooches would often hold a portrait or a lock of hair, while mourning brooches incorporated jet or black enamel to honor lost loved ones. These sentimental designs reflected the Victorian fascination with memory, family, and mourning rituals.

Brooches from this period were also influenced by the broader Romantic movement, with motifs like flowers, hearts, and serpents symbolizing love, eternity, and protection. Jewelry in the Victorian age was highly personal, and brooches became one of the most common ways to wear one’s emotions in plain sight.

Art Nouveau and Art Deco: From Nature to Modernity

At the turn of the 20th century, Art Nouveau brought a new spirit of design that emphasized flowing, organic shapes. Brooches of this period often featured naturalistic forms such as flowers, insects, and feminine figures. Enameling became especially popular, allowing jewelers to capture delicate hues and textures that mirrored the beauty of the natural world.

By the 1920s and 1930s, Art Deco shifted the aesthetic dramatically. Gone were the curving, asymmetrical forms—in their place came bold geometry, symmetry, and sleek modernity. Diamonds, platinum, and colored stones were arranged in strong, striking patterns that reflected the glamour and energy of the Jazz Age. Together, these two movements illustrate the incredible versatility of the brooch, adapting to capture both nature’s elegance and modernity’s boldness.

The Brooches of Today

In contemporary fashion, brooches are no longer confined to tradition. They are used as decorative accessories that allow individuals to express personality and creativity. Designers experiment with materials ranging from precious metals and stones to unconventional mediums like acrylics, plastics, and textiles.

Today’s brooches appear on runways, red carpets, and even in political symbolism, often worn by public figures to send subtle or bold messages. The enduring appeal of the brooch lies in its versatility—it can be personal, political, fashionable, or purely artistic.

While You’re Still Here…

If you have a brooch that needs a repair, you can be sure to trust it to the hands of our Master Jewelers right here at My Jewelry Repair

Check Out the Magic of Our Jewelry Services!

Resources:

- History and Evolution of the Brooch: https://rauantiques.com/

- A history of brooches: the evolution of style: https://www.thejewelleryeditor.com/

- ¹Bone Brooch: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

- ²Fibulae Brooch by LACMA, available at Wikimedia Commons

, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0: https://commons.wikimedia.org/ - ³Cluny – Mero – Fibule – VIIe siècle – Bronze, Or, grenat, verre – Lorraine puis MAN,” by Cangadoba, available on Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

- ⁴Roman zoomorphic brooch (FindID 496357), by The Portable Antiquities Scheme / The Trustees of the British Museum, available on Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

- ⁵Fibula de Braganza,” by Manuel Parada López de Corselas, available on Wikimedia Commons, released into the public domain under CC0 1.0: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

- ⁶Schwarzer Trauerschmuck1,” by Detlef Thomas, available on Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 DE.: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

- ⁷Mourning brooch containing the hair of a deceased relative,” by Wellcome Library, London, available on Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 4.0.: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

- ⁸“Golden Penda (Xanthostemon chrysanthus) in the heroes’ park,” by Margaret Donald, available on Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

- Blog outline and revising assisted by AI resources such as Google Gemini.